Turing Is Not Your Therapist

Turing did not intend to give comfort to the imprecise use of language about "thinking machines" for all time. The legacy of his Imitation Game is a bundle of misinterpretations.

Turing’s Overwhelming Success

A strong case can be made that Alan Turing’s work on the Imitation Game, primarily but not exclusively in his 1950 paper, was too successful. If Turing’s aim was to stimulate the practical effort to build intelligent machinery: Mission Accomplished.

The Imitation Game has since outlived its usefulness, by now harming the field with a legacy that I doubt Turing meaningfully anticipated. The popular reading of Turing in which one can use the language of “thinking machines” (or “reasoning machines,” etc.) without concern for these terms’ precise meanings or theoretical foundations has been wrongfully interpreted as a reason to avoid disconfirming evidence. Turing unwittingly plays the role of therapist for the distressed.

The Imitation Game In Brief

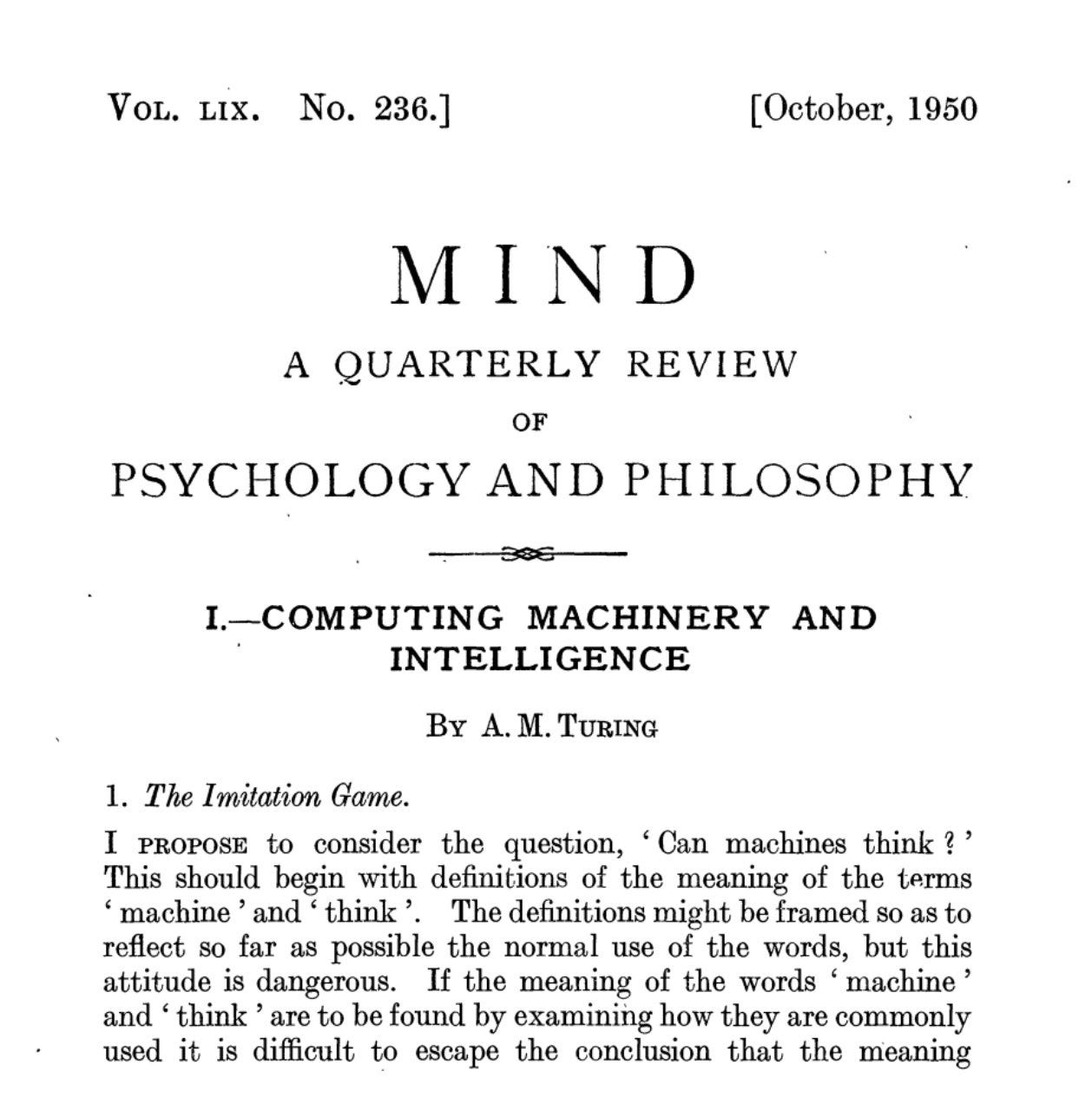

For those unfamiliar, the (popular) story is straightforward enough: In 1950, Turing wrote a landmark paper titled, ‘Computing Machinery and Intelligence.’ The paper’s explicit and opening aim is “to consider the question, ‘Can machines think?’ This should begin with definitions of the meaning of the terms ‘machine’ and think.’”

Turing, careful with his words, notes that these terms’ definitions “might be framed so as to reflect so far as possible the normal use of the words…” That is, how people ordinarily use them. However, given the difficulty in parsing this normal usage, he “shall replace the question by another, which is closely related to it and is expressed in relatively unambiguous words.”

The replacement question revolves around the “Imitation Game” —a game played at parties (at that time) where an interrogator is tasked with determining, by posing questions to two people in a separate room, who is the man and who is the woman. Turing wants a machine to be a participant in this game.

After some clarifications about the test’s parameters and what he means by a “machine” (he means a digital computer), he makes his way into what is likely the paper’s most famous passage. Turing informs us of his personal belief: “I believe that in about fifty years’ time it will be possible to programme computers, with a storage capacity of about 109, to make them play the imitation game so well that an average interrogator will not have more than 70 per cent. chance of making the right identification after five minutes of questioning.”

Immediately, Turing is telling us he believes that by the end of the century, digital computers will have advanced sufficiently to be effective at playing the Imitation Game.

Then comes this: “The original question, ‘Can machines think?’ I believe to be too meaningless to deserve discussion. Nevertheless I believe that at the end of the century the use of words and general educated opinion will have altered so much that one will be able to speak of machines thinking without expecting to be contradicted.”

He continues: “The popular view that scientists proceed inexorably from well-established fact to well-established fact, never being influenced by an unproved conjecture, is quite mistaken. Provided it is made clear which are proved facts and which are conjectures, no harm can result. Conjectures are of great importance since they suggest useful lines of research.”

What Do People Think Turing Is Saying?

These passages are interpreted, in popular contexts, as equivalent to the following tenets:

Machines, including digital computers, could in principle be made to “think.”

To define the term “think,” one should extract its meaning from its normal usage.

This is tedious and messy, however, so we instead replace the question ‘Can machines think?’ with the question, ‘Can a machine be made to succeed in the Imitation Game?’

It is apparent that, by century’s end, a digital computer will effectively play the Imitation Game.

It is therefore not necessary to precisely define terms such as “think” because, by century’s end, it will be normal to speak of “thinking machines” without a sense of contradiction.

Thus, we can speak of “thinking machines” without precisely defining “thinking.”

What Is Turing Actually Saying?

If we take Turing’s argument literally, it’s strange. He freely mixes his private beliefs about the possibility of a digital computer fooling an interrogator in the Imitation Game with his judgment that fooling an interrogator a certain amount of time is necessary to achieve the status of a “thinking machine.” But, he tells us, quibbles over this status are “meaningless,” since it will become normal to speak of machines this way by century’s end, so we need not worry about definitions. Yet, Turing began the paper by worrying about these definitions. And then…Turing goes on to spend the rest of the paper responding to criticisms of the idea that machines can think!

Perhaps, then, we should not take Turing’s argument literally. Turing was a human being. (We can forgive him for that.) Being human, and a particularly genius one at that, he probably had a bit more going on upstairs than his remarks in the 1950 paper, a few adjacent remarks between 1948 and 1952, let on.

Academic publishing norms have since changed, so mixing private beliefs in one’s scholarship as well as structuring essays in (almost deliberately) difficult-to-parse ways may be less common today than in Turing’s time. Yet, Turing was likely up to something more practical than intellectual.

This fantastic article by Bernardo Gonçalves, one of several from him, argues that Turing may have followed in Galileo’s footsteps by invoking the Imitation Game as a “crucial experiment” as a “concession to meet the standards of his interlocutors more than his own” while employing propagandistic rhetoric to advance research. (Indeed, the—likely apocryphal—Galilean story of dropping weights from the Tower of Pisa spawned centuries of inspired, practical demonstrations.) The Imitation Game, on this view, was a strategic move.

This is far from the only possible reading of Turing’s motivation, but it does help make sense of the essay’s internally conflicting structure.

Just as importantly, as James McGilvray takes pains to explain, Turing’s Imitation Game followed a long history of constructing tests for machine intelligence or possession of mind going back to at least Descartes. Yet, Turing’s was different:

One of the more important of those insights, usually ignored, is that if a machine does pass the test, no fact of the matter has been determined; no scientific issue is resolved. The test offers no evidence in favor of a specific science of mind, and it does not show that the mind works the way the computer that passes the test does…All that is claimed to follow is that success might offer a reason to decide whether to say that a machine thinks—to decide whether to change one’s use of language and say that machines think (now often done anyway, without satisfying anything as strict as Turing’s test).1

Indeed, as Noam Chomsky similarly notes, “it is idle to ask whether legs take walks or brains plan vacations; or whether robots can murder, act honorably, or worry about the future.” If I say that my laptop needs to “breathe” and proceed to clear the area surrounding its vent, we would not suggest that the laptop “breathes” in any meaningful sense that a biological organism “breathes.” An airplane “flies” (for English speakers), but submarines do not tend to “swim.” These are merely terms of ordinary language; they denote no technical meanings.

The misinterpretation of Turing’s 1950 argument is the belief that these terms were never meant to be clarified, refined, or couched within a sufficiently robust theory of biological or artificial intelligence. Hence, advocates who insist on using such terms as part of ordinary language are forced to defend human-machine comparisons we otherwise would go without.

Why Does This Matter?

As researcher Melanie Mitchell recently pointed out (and proceeded to write about in Science), it is becoming routine for major AI companies like OpenAI to refer to the activities of their models as “reasoning” and “thinking.” Indeed, when introducing the o-series last September, OpenAI said the models are “designed to spend more time thinking before they respond. They can reason through complex tasks and solve harder problems…” In a separate blog post, explaining why the chain of thought process cannot be intervened on by policy compliance (and therefore hidden), OpenAI notes “the model must have freedom to express its thoughts in unaltered form…”

You get the point. And one need not look far for other examples. In his New York Times article on his belief in the imminence of the Second Coming AGI, Kevin Roose says that when it

is announced, there will be debates over definitions and arguments about whether or not it counts as "real" A.G.I., but that these mostly won't matter, because the broader point - that we are losing our monopoly on human-level intelligence, and transitioning to a world with very powerful A.I. systems in it - will be true (emphasis added).

The general sentiment pops up elsewhere. Former OpenAI Policy Lead Miles Brundage claimed earlier this year that “Turing would find debates about whether language models are “really reasoning” very cringe. He tried to warn us.” Turing’s wisdom, Brundage explains, was to avoid getting “bogged down in terminological debates” and instead focus on “good operationalizations of “thinking” + test (for which the Turing Test was just an illustrative example).”

The underlying point (most clearly expressed by Brundage2) is valuable: terminological disputes really can prevent frontier research. A number of scholarly interpretations of Turing’s Imitation Game that somewhat diverge from Gonçalves nonetheless converge on this idea. Darren Abramson, for example, argued that Turing’s hang-ups about terms like “thinking” may have been an implicit acknowledgment that he had no alternative to an internal, sufficient condition for the possession of mind, but our lack of understanding in this domain “need not preclude scientific inquiry.” Hence, the use of the Imitation Game.

Yet, this point has since lost its luster. While Turing was right to try and bypass terminological disputes in favor of practical machine building by simply accepting the language of thinking machines, this has a concomitant downside once progress is actually made: when practical machines fail in unexpected ways - or their advancements along critical measures stall - advocates of designations like "reasoning" and "thinking" will find themselves retreating back into the human mind.

Why does the model fail on this edge case? Well, humans fail on that, too, and they reason, don't they?

Why does the autonomous vehicle crash into a wall? Don't humans crash as well?

Why does the agent make up these citations? Well, don't humans make things up sometimes?

You see what I'm getting at. The shift from “thinking” machines as a matter of necessity, to spur frontier research in a fledgling field, to using it to underwrite modern economies is a self-contradiction. The early adoption of the language of “thinking” machines was in order to progress. Once that progress is made, and individuals and companies try to extrapolate from existing progress to human-level capabilities, then we need to know what terms like “thinking” and “reasoning” actually mean because we might not be heading there. And, sure enough, when adoption is marred by technical shortcomings, those who insist that we use these once-reserved-for-humans terms without care for precise meanings or theoretical assumptions will find themselves at the start of the loop: that these are mere bumps on the road to AGI since we already have machines that can think and reason.3

When I hear these purportedly atheoretical caricatures of Turing’s 1950 remarks, I am reminded of philosopher Peter Ludlow, in a somewhat overlapping context, bluntly saying: “That’s the worst position of all.” If one adopts the position that, say, o3 is reasoning—and they explicitly say they do not need to define or otherwise locate “reasoning” in a theoretical framework—then their position amounts to a confession that they do not know what their theoretical assumptions are. Rest assured, they do have them.

The Cartesians thought differently about this. They believed their tests for possession of mind (one of which Turing at least knew about, and may have been influenced by) were probing for an actual property in the real world that we would call “mind.” The tests were scientific, rather than rhetorical. Should a subject pass the Cartesians’ tests, that—in their eyes—really would decide a scientific fact of the matter. That subject could now be said to possess a mind like ours; in possession of a substance that we share. Something to notice is how much less ambitious Turing’s Imitation Game is against this historical backdrop, resigning itself merely to a decision to speak of a machine in this or that way.

Though, he wrongly presents Turing’s view as monolithic and undisputed.

It also stretches credulity to its breaking point to assume that Turing envisioned the contemporary, multi-billion dollar AI industry and its remarkable ability to manufacture hype—in part by bending over backwards to make his predictions “come true.” Does it count as ‘ordinary’ language if its primary point of origin is c-suite executives and high-paid researchers?

Right. Wittgenstein is your therapist:https://www.perplexity.ai/search/what-wittgenstein-meant-philos-.If34W4RQSO0Ze1xYWIpYQ