Do Language Models Learn Like Human Children?

On a history of unwittingly lifting cognitive weight, with comments on a personal motivation for studying a very unusual topic.

There are periods when I begin writing and forget to stop. I am in one of those periods now. The flame burns bright around this time of year. Hopefully, this makes for pleasant end-of-year reading. Happy Holidays!

I attended a workshop at the University of Zurich back in June 2024 structured around a book, written by Matthias Mahlmann, called Mind & Rights: The History, Ethics, Law and Psychology of Human Rights. Possibly to the chagrin of some readers, Mahlmann, a legal scholar and philosopher by trade, adopted the Universal Moral Grammar (UMG) model of moral cognition in the book’s third section.

I was invited to the event because my initial foray into cognitive science was through moral psychology and its relation to human rights attitudes in International Relations (a type of political psychology). My interest in language was basically nilch, save for its usefulness as an analogue in the study of moral cognition.

At the time of the event, the state-of-the-art in Large Language Models (LLMs) was GPT-4o. I was, by that time, fully engaged with linguistics as it relates to these models. I therefore made this issue the topic of my contribution. If Mahlmann was adopting a theory I am largely sympathetic to, it would be extraordinarily uninteresting if I simply spent my time agreeing with him. I thus structured the paper contribution around the idea that a fundamental challenge to Universal Grammar via LLMs would be transformed into a challenge against UMG. So, we better get the computational modeling stuff in order.

I recall speaking with John Mikhail, an early intellectual inspiration for me. He expressed some understandable skepticism about the influence of LLMs in moral cognition. I suggested the LLM-mania in cognitive science would not stop, and any perceived success in linguistics would be used to dismiss the entire generative enterprise. You may judge for yourself if this is accurate.

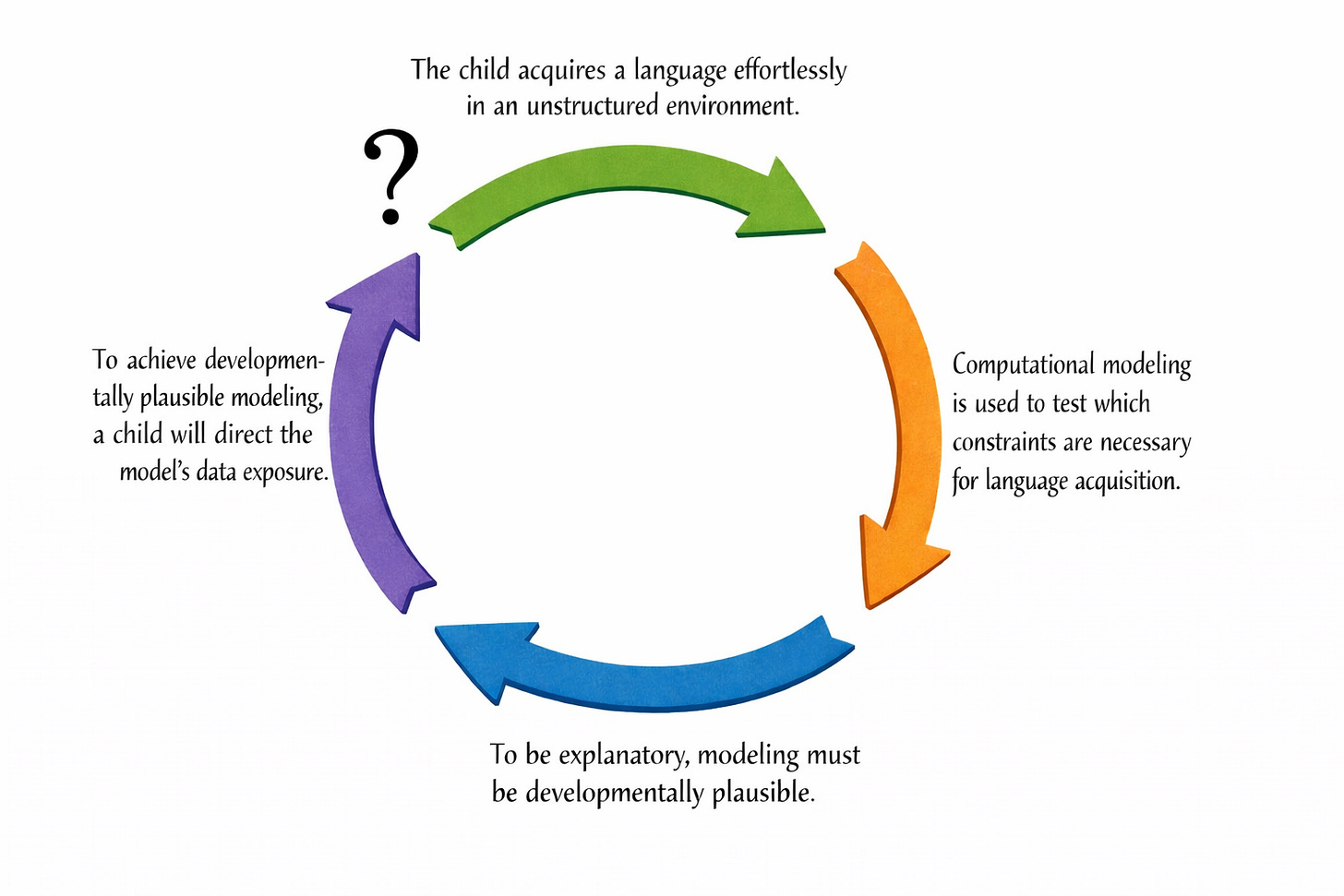

The paper I ended up writing tried to avoid familiar matters, like the poverty of stimulus arguments, that usually dominate this discussion. Because generativists have historically been less interested in computational modeling than their critics, there has not been a clear-minded attempt to stake out a position on the scope and limits of computational modeling. LLMs have somewhat forced this discussion, though I believe there is much more to say than has been said.

The nearly final paper is here. This piece aims to lay out in a more accessible format some key points about the uses and limitations of computational modeling in linguistics, focusing on: the format of the input to models and domain-specificity, the sequence of learning trajectories, the constraints on learning, and the means of data collection. A review of a case study on developmentally plausible ML modeling provided. I mostly avoid the talk of “voluntary” or “free” linguistic behavior that I usually discuss (“mostly”). There is also a detour to talk about apes.

The upshot on computational modeling:

The ways in which ML models are often used in cognitive science for explanatory purposes leads researchers to unwittingly perform heavy cognitive lifts on the model’s behalf, circumventing challenges otherwise faced by human children.

The upshot on LLM-mania:

The tendency to reduce explanation in computational modeling to a collection of human-like outputs from models bears resemblance to the reduction of linguistic complexity, and forgivingness of errors, in efforts to teach apes, like Nim Chimpsky, language.

Let’s get to it.

Format of the Input and Circumventing Domain-Specificity

First, the easy stuff. In particular, let’s consider how LLMs deal with the leap from “noise” to “language” and the sequence of their learning trajectories.

Consider a pre-LLM text: Lasnik et al.’s Syntactic Structures Revisited, published in 2000. There, they wrote:

The list of behaviors of which knowledge of language purportedly consists has to rely on notions like “utterance” and “word.” But what is a word? What is an utterance? These notions are already quite abstract. Even more abstract is the notion “sentence.” Chomsky has been and continues to be criticized for positing such abstract notions as transformations and structures, but the big leap is what everyone takes for granted. It’s widely assumed that the big step is going from sentence to transformation, but this in fact isn’t a significant leap. The big step is going from “noise” to “word.” (emphasis added)

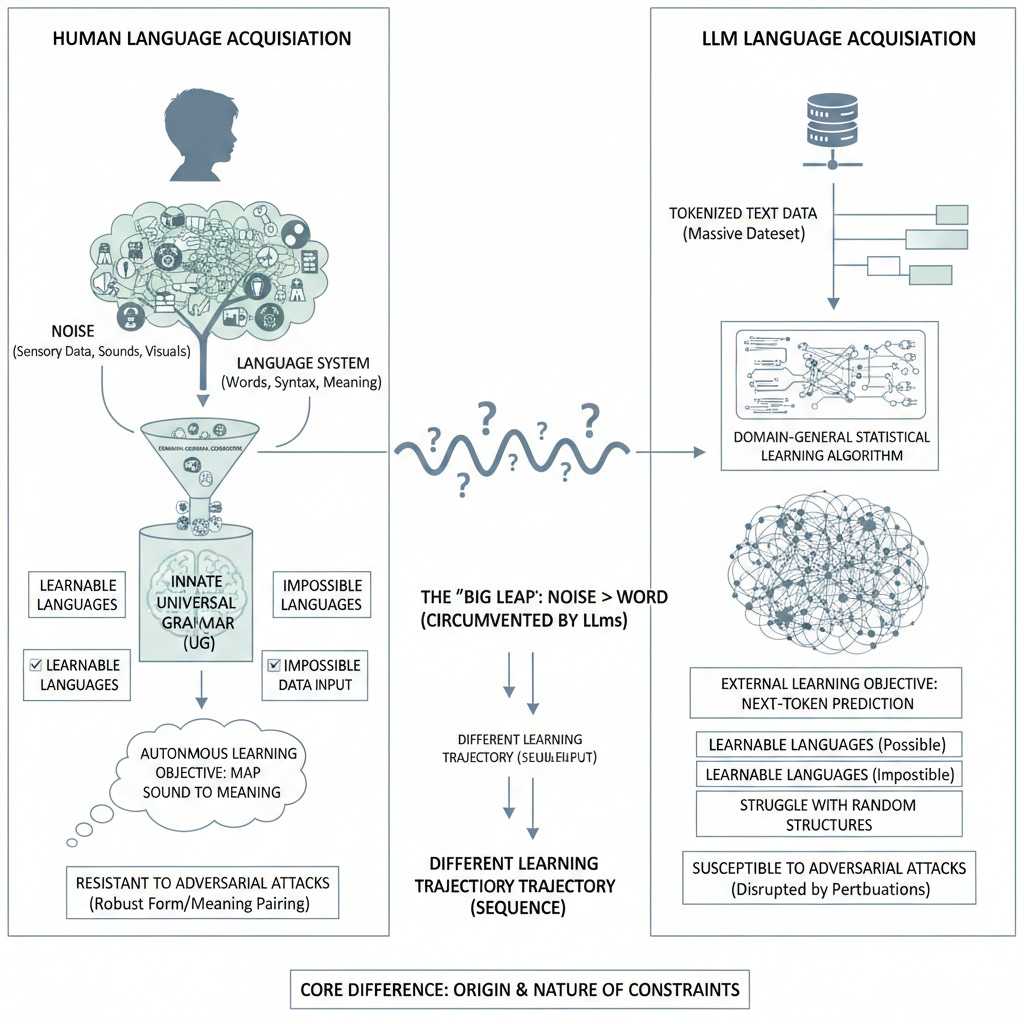

In this sense, the heavy cognitive lifting in language acquisition is between the jump from “noise” to “word.” This remark may be interpreted as a comment on the switch from domain-general to domain-specific; moving from “noise” to “language” is a specialized activity with which the child must contend.

LLMs circumvent this challenge.

LLMs process text via “tokens,” representing words or parts of words. Each token has a numerical value. During pre-training, the network predicts the next-token of a sequence of tokens (i.e., a sentence), the last of which is masked. The model learns the statistical correlations between the tokens it is pre-trained on. The model therefore does not “read” natural language text as words, a basic human linguistic unit.

For LLMs, there is no “noise” in the environment from which it must select relevant linguistic data. The data on which the model trains is the only data in the model’s “environment.” The identification of linguistic data is effectively circumvented via pre-training on text-based utterances and, in addition, tokenizing that text-data. There is no need to separate “noise” from “language,” as the linguistic nature of the data is scaffolded by the human engineers prior to when learning is underway.

LLMs do have a learning objective, but the means by which this objective is scaffolded by human engineers ensures that the heavy cognitive lift of moving from “noise” to “language” is circumvented.

One could object: humans do not face this obstacle of moving from domain-general to domain-specific, as all data in the environment is equal, as it were; there is no “linguistic” data before analysis of child development. To the child, it is all simply data, and they transform some of that data into what analysts call “linguistic” data.

However, this merely restates the original problem in new terms: the child must perform a cognitive activity in which they acquire a system that allows them to map sound onto meaning according to a peculiar structure. The data they select to do this may not have a “linguistic” pre-theoretical status, but this takes nothing away from the cognitive challenge they face. Some data is more relevant to acquiring this system than others, and the child must successfully navigate them.

Sequence of the Learning Trajectory

The data that LLMs train on is unstructured. However, the sequence of their learning trajectory differs in two ways from humans.

First, they learn language through text-data (tokenized), in contrast to children who learn from raw sensory data in the environment, like spoken language, before learning to read.

Second, many of these data are rich linguistic texts, quite diverse in nature (textbooks, essays, shitposts, etc.). The model learns from this data in a hodgepodge fashion. As I wrote: “It is as if we were to suggest that human children read A Tale of Two Cities before learning to speak.”

An LLM’s learning sequence is thus not developmentally plausible.

Statistical Learning Relies on a Restricted Hypothesis Space

Some researchers will make the following point: yes, LLMs are trained on linguistic data that was generated by humans, but…so are humans!

One can see how an argument about the power of domain-general statistical learning proceeds from here: if the LLM is learning “like” the child in that it merely is exposed to linguistic data in its local environment, then the fluency of LLMs indicates that these models are an existence proof of language acquisition via statistical learning.

Before we proceed, a refresher.

Back in the early 2000s, there was a burgeoning enthusiasm for statistical learning methods in language acquisition. A classic article in this debate, from the pro-UG side, is Charles Yang’s “Universal Grammar, Statistics, or Both?”

Yang argued that any effective learning algorithm must appropriately represent the relevant learning data. Thus, the claim that infants statistically track information as they are exposed to it during development “must presuppose that children know what kind of statistical information to keep track of.” Yang is saying that, whereas there is a range of possible correlations of linguistic data an infant could track, they instead only ever learn a restricted range of these. Thus, this range is constrained from the get-go by an innate, domain-specific endowment, ensuring that the child’s (statistical) learning operates over specific aspects of the inputs in its environment. (It is domain-specific because the constraints are imposed on only one, specialized form of cognition.1)

Computational modeling poses such a vexing challenge because it seems that LLMs easily refute Yang’s argument, namely, that only domain-general statistical learning is needed. Why? Because LLMs appear to learn language by tracking statistical correlations with a domain-general learning objective! (Next-token prediction is domain-general because it operates over a training dataset with no linguistic-specific principles that constrain it; the learning objective is agnostic to the dataset, as it were.)

However, LLMs partly circumvent the human challenge.

The problem is one that unfolds at several stages of model development. It is related first to the fact that humans provide the training objective with which LLMs acquire a statistical representation of their training data. Consider: the training objective constrains the LLM to a particular set of statistical relationships, even though these constraints are domain-general in nature.

Computational modeling effectively replaces genetics (or what have you) in human development with human engineers - the instantiation of a next-token prediction training objective is akin to genetic instruction in humans. That it was provided from the “outside” prior to training is irrelevant. LLMs specifically, trained on domain-general next-token prediction, are therefore evidence against the notion of domain-specific constraints like UG.

Still, this would have us conceive of LLM training as equivalent, or sufficiently analogous, to a child: exposed to data in their environment, the model and the child learn language via internal, domain-general learning objectives (the former provided by humans, the latter by genetics/biological makeup).

But the LLM is not equivalent, or sufficiently analogous, in this respect. Tying in with the previous point, the tracking of statistical correlations occurs over a dataset in which “language” has already been distinguished from “noise” through tokenization.

More than this: the model’s ability to learn anything of interest by predicting the next token depends on the dataset having a “correct” answer, or ensuring that the masked token in the sequence is part of a structured product originally produced by humans for which there is an unambiguous answer that it can use to update its weights. A human child cannot be said to learn this way, and any child that does not learn this way is a refutation of the idea that LLMs are adequate models of human language.

Put differently: the statistical learning of an LLM is constrained by the closed-set of language-specific data over which it operates. The learning algorithm appropriately represents its target data in part because human engineers have sharply limited the range of possible correlations these models can acquire over a massive training dataset; the hypothesis space has been narrowed. Statistical learning does not bridge the gap, so much as it enters the scene after the stage has been set.

There is a heavy cognitive lift involved here, but the model circumvents it.

LLMs Are Differently Constrained in Production

Possible and Impossible Languages

LLMs are not subject to the same constraints as human learners. This point does not relate to the origin of the learning objective. Rather, the point is that human brains appear to impose certain constraints on what is learnable in given domains, like language, constraints to which LLMs do not appear subject.

Thus, one finds arguments in the relevant literature about whether LLMs are capable of acquiring “possible” or “impossible” languages. I cannot do the concept justice here, but whether LLMs acquire these is a proxy for two competing positions: (1) LLMs cannot acquire impossible languages and are therefore similarly constrained; (2) LLMs can acquire impossible languages and are therefore not similarly constrained.

Chomsky et al. made the following assertion in The New York Times in March 2023:

But ChatGPT and similar programs are, by design, unlimited in what they can “learn” (which is to say, memorize); they are incapable of distinguishing the possible from the impossible. Unlike humans, for example, who are endowed with a universal grammar that limits the languages we can learn to those with a certain kind of almost mathematical elegance, these programs learn humanly possible and humanly impossible languages with equal facility. (emphasis added)

The claim of “equal facility” was no doubt made prematurely, likely on the basis of other deep learning architectures that were making their way through linguistics.2

Kallini et al. (2024) nevertheless took it upon themselves to prove Noam wrong. In a piece titled, “Mission: Impossible Languages,” they train GPT-2 models and share three findings: (1) models trained on possible languages learn more efficiently; (2) the models “prefer natural grammar rules”; and (3) the models develop human-like solutions to non-human grammatical patterns.

Notice that these models had, in fact, acquired impossible languages, albeit less efficiently. It was therefore odd for the authors to frame their results contra Chomsky.

Bowers & Mitchell (2025) noticed this in a brief review of the literature, noting that the impossible language most difficult for GPT-2 to learn was a language in which the words in sentences were arranged randomly. It is unclear what the relevance of struggling on that particular language is supposed to be for the constraints posited by UG, as it lacks any structure to learn at all. This is also picked up by Bolhuis et al. in a commentary on a target article published by Futrell and Mahowald, noting that the computational complexity of an impossible language could also account for difficulty in learning certain impossible languages tested by Kallini et al., rather than indicating human-like constraints.

The point is therefore to pay attention where the constraints differ; where LMs differ in their learnability from humans. Should a language that cannot be acquired by humans be learned by LMs, this indicates divergent constraints

It is therefore relevant when, for example, researchers extend Kallini et al.’s test of impossible languages by training a transformer-based LLM on the latter’s original perturbed versions of languages, add an additional perturbation across English, Italian, Russian, and Hebrew, and find that several of the impossible languages were easier for the model to learn using the same metric. This was Ziv et al.’s (2025) finding. (Note that this separate from another Ziv et al. piece, here.3)

Adversarial Attacks

Another line of thought (more interesting in my opinion) comes from David J. Lobina in an article and within a forthcoming volume concerning the relevance of adversarial attacks for LLMs’ linguistic competence.

Surprisingly, this source of evidence has not gained prominence as a means of testing the linguistic competence of LLMs. Still, it shares in common with the possible/impossible languages debate that it must be done while the model is in production. It makes a claim about what the underlying model has learned as a result of their susceptibility to adversarial attacks; the failure mode is revelatory. Lobina argues that perturbing the model’s input data in ways that are either imperceptible4 to humans or bizarrely inhuman is revelatory of what they have learned.

Adversarial attacks are revelatory because these perturbations effectively ‘disrupt’ LLMs’ language comprehension, such that they begin outputting text that is either incoherent or in direct contradiction with their own, earlier professions. Lobina argues that an explanation for this peculiar failure mode is that LLMs do something closer to what they are consciously trained to do: they model text-data. A learned statistical representation of text-data would entail that the model’s failure modes are defined in relation to a different set of capabilities and limitations relative to humans, who appear immune to adversarial attacks. Humans, rather than modeling text-data, regulate form/meaning pairs through natural language; a different capacity with different limits.

A Wall Street Journal video on the use of two Claude models to run the newsroom’s vending machine was mocked on Bluesky, in part because the jailbreaks used to bypass its instructions were ridiculous. But these mistakes are only ridiculous because we would never make them. The point is worth emphasizing - developmentally typical humans do not have their linguistic comprehension disrupted through carefully crafted utterances in their local environment. It is is not that it happens uncommonly; it does not happen, save for neurological impairments and the like (which is not reflective of normal linguistic competence). That the models did make these errors are datapoints, and taken together with trendlines from the past few years, are revelatory of the limits of their learned representations of the data it is trained on. Those limits are different than our own, defined in relation to different capabilities (many of which we also do not share).

It is worth pausing for a moment to recall: theory in science operates according to inference to the best explanation, or abductive reasoning. It often seems as though those favoring computational modeling in explanatory theory have forgotten that it is incumbent upon them to offer the best explanation for all relevant data. Selecting which data are relevant is no easy feat, though it helps when critics point them out.

Here, we have a phenomenon that is both linguistically interesting and one that has persisted throughout the generative AI boom. LLMs that improve along certain measures nevertheless continue to fall for bizarre input data, leading them to output nonsense or harmful information. The proponent of computational modeling must offer an explanation for this that is better than suggesting the LLM is a model of text-data, which is why its 'comprehension’ is so readily - and inhumanly - ‘disrupted’ by data that has no such effect on humans.

Developmentally Plausible ML is Parasitic on Human Autonomy

Child-Directed ML Learning

Several efforts have been undertaken to develop small-data ML models; models that are developmentally plausible models of human language acquisition.5 These efforts are often framed in response to a recurring nativist criticism: that LLMs are trained on inhuman amounts of data.

The most striking of these efforts is detailed in a 2024 report in Science. The report, written by Vong et al., details how a long-standing problem in philosophy and cognitive science is how children who learn new words are presented with a “potentially infinite set of candidate meanings.” How the child quickly learns to associate words with objects correctly is thus subsumed by the debate over whether they require domain-specific constraints, or if domain-general cognitive mechanisms will suffice for acquiring word-referent mappings.

They proceed to ask:

If a model could perceive the world through a child’s eyes and ears, would it need strong inductive biases or additional cognitive capacities to get word learning underway? Or would a simpler account driven by associative learning, in conjunction with feature-based representation learning, suffice?

How they test this is striking: they strap a lightweight camera to the head of a child, beginning when the child is 6 months old and ending at 25 months old (1.5 years total). Throughout this period, the camera captured roughly 1% of the child’s waking hours, coming out to over 600,000 video frames and 37,500 text transcriptions of associated utterances.

With this data, they train a multimodal ML model called Child’s View for Contrastive Learning, or CVCL. It is trained via self-supervision.

After training, CVCL is given two tasks: first, the model was to select from images in the original dataset and match a word with an image. In the second, the model must pick from images not within the original dataset and were thus novel to CVCL.

On the first task (original dataset), CVCL scored 61.6% accuracy. On the second task (novel dataset), it scored 34.7% accuracy. The level of chance was 25%, meaning CVCL exceeded chance in both tests.

Vong et al. saw this as intervening on debates about nativism and language acquisition, auguring positive results for the thesis that “learnability with minimal ingredients…are sufficient to acquire word-referent mappings from one child’s first-person experiences.”

CVCL As a Tour de Force in Unwitting Cognitive Lifting

Although CVCL is among the more adorable ML experiments, the researcher’s have unwittingly lifted quite a heavy cognitive weight on this model’s behalf.

First, the data on which CVCL is trained was collected by the child and for the model. The model is effectively piggybacking off the data collection conducted by the child who navigates her environment autonomously.

Remember: the child is the baseline comparison in that she possesses the capacities for language acquisition that linguists are interested in. CVCL is meant to for this end.

Recall the earlier point made about tokenization (in LLMs) and domain-specificity: for an ML model, the only data in the “environment” is that provided by humans. Although that data may be unstructured, I believe many computational linguists have incorrectly conflated unstructured data with data collected in an unstructured environment.

This does get to a serious point: children do not passively absorb data in their environments. Forget how much data there is for a target domain. The data in the child’s environment may as well not exist if the child is incapable of selecting the relevant ones. In contrast to an ML model, a child’s local environment is unstructured, and it is up to them to figure out what’s relevant.

CVCL circumvents this cognitive lift. It relies, in the first instance, on the child’s autonomous exploration of her local environment, and in the second, on text transcriptions provided by the researchers. It seeks out nothing and, in the best case scenario, it “finds relevant” only what the child finds relevant.6

Relatedly, CVCL does not overcome the limitations of transformers in that it is not trained on raw sensory input. Rather, it is trained on video frames. The child navigates autonomously in a fluid and dynamic environment without the benefit of static and curated data. In contrast, CVCL deals with linguistic data that have been isolated and frozen, somewhat akin to tokenization in transformers.

We thus re-consider Vong et al.’s original question:

If a model could perceive the world through a child’s eyes and ears, would it need strong inductive biases or additional cognitive capacities to get word learning underway?

Maybe - but CVCL does have at least one strong inductive bias: the child’s behavior. If the goal of explanation is to determine whether the child’s own inductive biases are “strong” or domain-specific, then this determination must be made either prior to or independently of computational modeling that relies on the child’s behavior!

The closer one looks at this experiment, the more influential the humans behind the scenes become. It is also clear why some are tempted to level the charge of circularity.

Autonomy and Data Discernment by Humans and Models

There is a leftover itch that needs to be scratched here, most closely related to the foregoing remarks on CVCL. Usefully, a paper uploaded to ArXiv in August questioning the role of symbols in the age of deep neural networks sparked some discussion on Bluesky relevant to this. Among the authors was Tom McCoy, who responded (quite generously) to comments on this piece on Bluesky. The actual paper is not our concern. Consider his remarks:

In ML models, some training examples are more influential than others, so you could say an ML model can “decide” to ignore some data. In that sense both model types decide which data to learn from, but they differ in what criteria they use to do so.

…

Definitely true that LLM-style models can’t go gather new data (they’re restricted to focusing on a subset of their input), but it doesn’t feel outside the spirit of ML to allow the system to seek new data which it then applies statistical learning over, if seeking is also statistically-driven.

There is something to this. In particular, the idea that neural networks (like CVCL) can be said to discriminate, in a narrow meaning of the word, among their training data, in this way assigning more importance to some data points than others.

The question for explanatory cognitive science purposes is: does this data discrimination bear any resemblance to child data discrimination? I believe there are two obstacles in the way of this.

First, when a child discriminates among data in the environment, they act, as noted, in an unstructured environment, where the linguistic information is raw sensory input; there is no scaffolding done on the child’s behalf by other humans, including no externally-given means of data collection. The child determines which data are relevant on their own accord, according to some internal learning objective.

In sharp contrast, CVCL is not learning from raw sensory input, nor is it learning based on its own means of data collection. Text transcriptions are cognitive circumvention of no small measure. So, too, for the fact that the data on which it trains has been frozen in the form of video frames. Most importantly, CVCL entirely circumvents the need to judge for itself which data in the environment are those of significance, a feat instead performed by the child.

In the best case, CVCL learns word-referent mappings exactly as the child learns them, but only having learned these mappings because the child directed the data collection on its behalf. (Even this strong interpretation cannot be assumed, as CVCL could (and I wager, did) associate words and objects differently than the child.7)

Second, the updating of weights in a neural network during training may be usefully described as a narrowly autonomous activity (see, this piece), but this is a different kind of activity that what the child undertakes. The network’s training is closed off from other possible factors in its local environment. Just as with the case of LLMs and statistical learning objectives therein, CVCL by its very nature engages with a training procedure whose possible outcomes have already been constrained by human engineers.

Indeed, the human engineers have further offloaded the heavy cognitive lift of moving from “noise” to “language” by making CVCL’s training dataset dependent on the child’s behavior - who is the baseline target of inquiry.

The explanatory burden placed on the cognitive scientist is to explain why only one of these subjects - the child - acquires language without a guide to the selection of relevant data and without the isolation of relevant linguistic data in the environment into a frozen form, whereas the model requires both to even begin learning.

The target of the cognitive scientist’s explanatory burden is to identify the cognitive architecture that supports the child’s ability to engage in these behaviors. Different behaviors may be supported by different cognitive architectures, and determining what lies underneath behavior cannot be done simply by replicating behavior. It may in fact be worse to aim for higher accuracy, as failure modes are more revelatory of underlying capacities than perfectly reproduced behaviors, at least insofar as these experiments are carried out without clarity on the research design’s relevance to explanation.

We begin to see why so often in cognitive science debates about computational modeling return the question: what are we actually trying to explain here?8

Unwitting Cognitive Lifting and Nim’s Revenge

During the hey-day of “ape language” studies in the twentieth century - efforts to teach apes to learn human languages - one of the stars was a chimp named Nim Chimpsky (no relation to the linguist).

Among the researchers involved with the project was one Herbert Terrace, who got in the ape language game in part to prove wrong the thesis that only humans could learn language (among biological organisms, at least).

In a bit of scholarly schadenfreude, Terrace eventually became convinced that the ape language enterprise was chasing a dead end.

More importantly, though, is Terrace’s finding that researchers would often construct their experiments with apes in ways that invariably gave them a leg-up; to make their gestures (since they cannot speak) look more like sign language than they really were. Among these was a tendency for researchers to subtly prompt Nim “with appropriate signs, approximately 250 milliseconds before he signs” in order to provide the chimp with the contextual resources it needed to sign in response.

By 1982, Terrace sounded like the Gary Marcus of ape language studies, writing in The Sciences:

A chimpanzee who could sign creatively and reliably, in the sense that such constructions as water bird and more drink were typical of all of the ape’s adjective-noun constructions, would indeed have taken a giant step toward mastering a grammar, the most important feature of human language.9

Echoes of today’s debates about whether LLMs imitate and interpolate based on their training data, or if they genuinely innovate, jump out from this same article:

A deaf child’s use of sign language is just as spontaneous and non-imitative as a hearing child’s use of spoken language. Why even argue that an ape can construct a sentence (through whatever grammatical devices [American Sign Language] affords), if the ape’s signing can be explained by the simpler process of imitation?

…

Like Patterson (and other sympathetic observers of an ape’s signing), Montagu fails to distinguish between the meanings a human onlooker might project onto the utterances of an ape and their actual nature. (emphasis added)

Reading research articles published from Koko the Gorilla’s language education is similarly revealing (and quite a trip). “Koko experienced two language growth spurts between the ages of 2 ½ and 4 ½,” reads one report, “when 1) the number of signs in her vocabularly increased substantially; and 2) the mean length of her utterances (MLU) also increased substantially.”

It is likewise interesting how the authors of the same article rationalized their findings. They argue that Koko’s linguistic development is “parallel [to] that of the human child learning language,” but Koko’s learning, they note, was significantly slower, prone to plateauing more quickly. “At first glance,” the authors write, “this lower level of achievement might seem to b explained by the single fact that Koko is a gorilla and not a human.” Fear not, however, as “Koko’s tested IQ is at a level in which a child’s language development would not be delayed.” (This was published in a scholarly journal.)

Thus, Koko’s slower development owes instead to a more limited social environment, different attention span, motivational level, and activity from that of a human. (Hey, if it sounds like science, it is science.)

Penny Patterson, Koko’s primary caretaker, was also known for chalking up many of Koko’s improper signs to playful behavior (oh that Koko!).

By 2015, then an elder gorilla, Koko advised world leaders at the UN Paris Climate Conference, imploring them through sign language to save the planet, telling humans she has “love” for them but that they are “stupid.”

One does not need to squint to find a similarly forgiving attitude about LLMs today, among researchers as much as the hype-y folks. Something like this is happening in much of computational cognitive science, where the effort to explain human language requires that one reduce its complexity and the cognitive weights (that human children must lift on their own volition) to something that amounts to a collection of structured outputs. I doubt it’s intentional, and there is always the force of momentum behind a research agenda (sunk costs, academic tenure, prestige, ideology, etc.). But it’s there, and there is enough precedent to be wary of the conclusions drawn.10

Targets of Inquiry Are Not Self-Evident

Insofar as LLMs pose a challenge to nativist linguists, this challenge is not identical to the ape language challenge. LLMs output what appear to be well-formed sentences in natural language. Indeed, unlike ape sign language, these outputs are reliably well-formed, not dependent on exotic prompting, nor does this apparent structure break down throughout the course of a user’s interaction with the system (which is separate from the coherence of the outputs; their meanings and appropriateness).

That said, many of the remarks above on the disanalogies between human and LLM learning adopt the computational cognitive scientist’s core assumption: that the reproduction of well-formed sentences - apparently by whatever means works to accomplish this - is what matters in a science of human language.

Yet, the target of inquiry in linguistics is not self-evident. The nativist continues to be a grump about computational modelling precisely because they are interested in determining whether a system under investigation possesses the same underlying structure; that the generative linguist’s target, for example, is the knowledge or understanding of grammar means that a reproduction of well-formed sentences is insufficient for explanatory purposes. The process leading to these outputs may be incomparable to that of humans. It may also be uninteresting. As I quoted Chomsky in a previous piece, the “substantial coverage of data is not a particularly significant result” and this result “can be attained in many ways, the result is not very informative as to the correctness of the principles employed.”11

Even having taken the assumption for granted that replication is all that matters, experiments have a way of losing their significance once examined closely. Computational cognitive scientists, following in the footsteps of ape language studies, are repeatedly lifting cognitive weights on behalf of the models in question in ways that diminish their explanatory significance.

As I more clearly lay out in the workshop paper, the sequence of factors that I have pointed to there - the format of the input, the sequence of the learning trajectory, the constraints on learning, and the means of data collection - should rightly be seen as highlighting a qualitative mismatch between humans and machines that signal fundamental differences. This mismatch appears to revolve around the autonomy of human learning, a point to which we have continually returned.

And, as I argue in the paper, the clearest manifestation of this is that human children, beyond all of the heavy cognitive lifting I have illustrated here, as a matter of normal development begin to use their language in ways that are stimulus-free, unbounded, yet appropriate to the circumstances of their use - an ability so sharply inconsistent with the nature of computational models as stimulus-controlled, functionally-oriented phenomena as to make claims about shared cognitive architecture suspect.

Behavior is only ever a clue about cognition. Behaviors this distinct deserve more scrutiny.

Domain-specificity can be thought of as an orientation of the mind (of any species) towards a peculiar way of thought; the word “specialized” here denotes the access to specific forms of thought afforded by specific constraints on learning.

RNNs perhaps? I’ve seen it suggested elsewhere.

This piece also introduces a very useful framework for thinking about LLMs in linguistics: LLMs-as-Proxies (for theories) and LLMs-as-Theories (in themselves).

The imperceptibility of input data perturbations is a holdover from the days in which most such attacks were conducted more often against vision models, but the basic point holds.

You might notice that these efforts are often undertaken by researchers who clearly believe large models are (somewhat?) viable models of human language. There’s some cloudy conceptual thinking going on in this area.

And, I would argue, it does not even meet this bar; there is no guarantee that the model learns from the same input data the same way as the child. Even if it scored 100% on word-referent mappings on both tests, we still could not make this judgment!

Peculiar failure modes are as revelatory here as they are in LLMs.

Usage-based approaches that do not rely on computational modeling are in fact stronger than those that do. The reason is simple: the cognitive circumventions where are discussing here means, most basically, that such models are not existence proofs of language acquisition that are relevant to human development. (This of course assumes the computational linguist’s conception of explanation as a reproduction of certain properties of natural language, which I firmly reject.) Avoiding this modeling in foundational disputes allows the usage-based theorist to maintain necessary distance between the explanation - which is not merely a re-statement of a phenomenon - and the target of explanation - the child.

Nim was noted to have created new words, like “waterbird.” Turns out he was just pointing at things, and associating the relevant sign with the relevant object/animal (sometimes one after another, hence, water….bird). But what Terrace was saying is, the bar was so low, that if Nim produced constructions like waterbird reliably, even that would be progress.

For what it’s worth, I am aware of the recently deceased chimp Kanzi. There is also a claim made, separately, that bonobos exhibit compositionality. Space prohibits me from saying more, but you could probably guess what I’d say. In any event, I think the ape language case is substantially weaker than cases made out of LLMs, if revealing of similar tendencies among researchers to diminish the phenomenon in question. See here.

And, as Fodorian Brett Karlan argues, if one wishes to be justified in their judgments about the implications of empiricist AI for cognitive science, they must not only permit but encourage the development of an alternative, comparably resourced nativist research program in AI.