Better Than Chomsky

I will not make a habit of this, but a personal history is sometimes worthwhile. Here's mine.

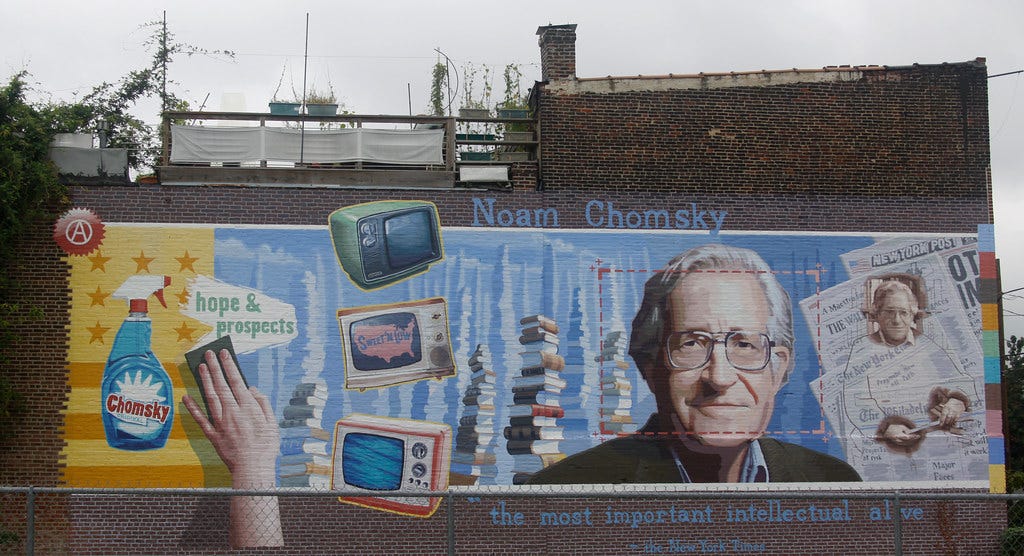

I first became aware of Noam Chomsky’s political work in high school. Perhaps unsurprisingly for a student self-loathing of the “honors student” status, I found Chomsky’s political writing cathartic. I disliked authority. I had opinions about it. I also had an interest in politics. The favorable encounter was natural.

At the same time, I developed a passing, completely amateur interest in moral psychology. Understanding the nature and source of moral judgments seemed to me a logical extension of being interested in politics.

Interestingly, I had zero interest in Chomsky’s linguistic or philosophical work in this respect. As any ignorant person might, I picked up a copy of Jonathan Haidt’s The Righteous Mind and assumed - wrongly - that I was reading an accurate depiction of the field and what it means for American political divides.

In that book, Haidt lays out his views on Social Intuitionism - that moral judgments are essentially generated in the process of social interactions, particularly during attempts to persuade others of the correctness of a particular moral view. These judgments derive from “moral foundations” (a theory goes by the same name) that are innate and comprise the psychological origins of these moral judgments. And here’s the kicker: while these modules are innate, they offer only a partial draft of the moral mind. The rest is filled in by experiences. Different groups within societies assign different weights to this or that moral foundation.

Ah! What an intuitive explanation presents itself for American partisanship: whereas the American liberal emphasizes moral foundations like “care/harm,” the American Conservative instead emphasizes moral foundations like “authority/obedience.”

I was content with this explanation. I could only digest a little “innateness,” and leaving room for experience to guide human life - seemingly giving individuals some choice in the matter - was acceptable.1

During this same period, I came across an interview where Chomsky was asked about linguistics. I distinctly recall listening to him talk about the “discrete infinity” of human language and the ‘unbounded capacity for creative expressions.’ My reaction at the time was: ‘that sounds interesting, in the way an exotic topic might be, but whacky. I really have no idea what the hell that means.’

So, I checked out of that topic for at least 3 or 4 years.

Several years later, while I had kept up with Chomsky’s political work as an undergraduate student, I became somewhat less attached and less interested. Studying political science meant there would be a dose of, let’s say, antipathy to anarcho-syndicalism. I was also studying philosophy, with an interest in moral and political philosophy, though my earlier interest in moral psychology had been dropped.

I happened to take a course called International Organizations in my sophomore year of college. During this course, we covered the 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights. As you would expect, the readings for that week surveyed how each of the dominant approaches to International Relations - Realism, Constructivism, Liberalism, and (sort of in the corner by itself) Marxism - explained the Declaration.

I found these approaches deeply unsatisfying. Take a moment to see how distinctive the Universal Declaration actually is: exactly one species has had a world war (and two of them at that!). After the second, representatives from different groups in the species deliberately recruited people with ideologies and philosophies that have radically different foundations. These people then developed a specific list of “human rights” that would serve as the standard of civilization, apparently specific to the species, and agreed on it.

What an absolutely bizarre phenomenon!

And what does one do, when faced with the inadequacy of the discipline they are studying? They email Noam Chomsky!

So I emailed him, knowing that he was involved in both politics and cognitive science, and asked whether he had any thoughts on this whole Universal Declaration business. (If memory serves, I may have come across this little-noticed lecture by him and Elizabeth Spelke on universality in linguistics and human rights at some point.) He referred me to John Mikhail’s Elements of Moral Cognition, a book arguing for a theory of moral cognition modeled (naturally) on Universal Grammar in linguistics.2

Long story short, I did not buy the book, because it was $80, and I was a poor student. Though I did look into Mikhail’s work extensively thereafter.

The rest is basically history. You know where I stand on the UG and UMG business now if you’re subscribed to this.

But this isn’t to say that the transition from my earlier beliefs as a high school student reading Haidt’s work to the beliefs I hold today was ‘natural’ or comfortable. I in fact resisted the notion that “innateness” is a meaningful factor in human life, though I found it interesting that someone like Chomsky would advocate for radical changes in political life while also insisting on innateness in his linguistic work.

If I had to pin down the source of my discomfort with the idea at the time, I might describe it as a desire to see a (small-c) constructivism about human affairs vindicated. The commonsense notion of science as an act of filling in the causal gaps in life, leading anything of meaning to become a receding horizon, in part meant that science was a hurtful activity.3 It promised to steal the instincts worth acting on. “Innateness” was its logical extension.

I did, eventually, get from there to here. A significant step in doing so was dealing with the extremely uncomfortable knowledge that I was not really paying attention to the ideas I was reading, so much as the ideas I instinctively favored, inappropriately overlaid onto the source material.

Such intellectual transitions are emotional. And in my experience as an outsider learning and - because I am seemingly unable not to do so - engaging with cognitive science and philosophy, I have sensed a similar discomfort with the idea of “innateness.” People are made uncomfortable by the idea, to say nothing of the fact that individuals have epistemic tastes which meaningfully influence their feelings of competing approaches - approaches that are often only “competing” because the individual was attracted to a particular flavor of idea in the first place.

If one allows it, this discomfort never ends, as critiques from without or within are always forthcoming. The trick is to become comfortable with the bizarre.

I benefit - if I can speak bluntly, which I can - from two instincts: I cannot tolerate self-pity and I cannot tolerate the knowledge that I might be wrong about something important to me;4 I have to at least give it a go.

Noam Chomsky decided at some point, seemingly after the passing of his first wife, to make a moral disgrace of his life. Others will say it happened much sooner. Maybe. There seems to me a difference between even atrocious views on American foreign policy and associating closely with Epstein, in such a way as to stretch credulity - as though Chomsky was not clever enough to know who he was dealing with.5 Contrary to one of his defenders, he did in fact suffer fools.

I do not have tolerance for this. It is bullshit.

I likewise do not have tolerance for those who pretend that Chomsky’s association with Epstein has any bearing on his linguistic or philosophical work whatsoever - work which they, for reasons likely having to do with their epistemic tastes, despise. This stretches credulity in a different way - as though those who decided Chomsky was “wrong” 20 years ago today judge the actions of a disgraced man neutrally.

This, too, is bullshit, as though I should defer to a mix of forced outrage and the unstudied epistemic instincts of others, and ignore how infrequently the more difficult paths are followed.

I understand what it’s like to deal with uncomfortable ideas. None of the ideas that the high school version of myself came into contact with exist in any recognizable form in my mind today. The theme has been one of seeking out the bizarre nature of commonsense phenomena, finding that the discomfort that comes with this is always worth wading through. Find the value in counter-intuitive ideas, keep an eye out for the bullshit. This works well enough.

The baseline that Chomsky’s reflexive intellectual critics insist upon is to be better than him. They are right, and I do not have tolerance for anything less. That this should come at the expense of one’s honest assessment of hard problems in cognitive science and philosophy - which, conspicuously, they had also insisted upon for years prior to recent news - is an avoidance that I cannot tolerate.

If you pay attention, you’ll notice views like this forever stretch the space for experience to make a substantive revision over that ‘first draft.’

The book is, for what it’s worth, extremely rigorous. A no-nonsense, extended explication of UMG.

Like so many things, this commonsense view is basically unrecognizable to me today.

This instinct can destroy a person who does not manage it, as it seems to have done to Derek Parfit.

Worth noting, for those unaware, is that Chomsky was chummy with Epstein, but as far as I know has never been accused of criminal activity (this could change in future releases). I suspect Chomsky deliberately remained ignorant, which is bad enough.